CAMEL #3

Essay on Alex Grey, Review of Orion Martin at Derosia, Market digest, Hilton Kramer vs. Contemporary Art (1995)...

Hi,

Welcome to the third Camel, my newsletter covering a variety of art-related and Grant-Tyler-related topics. I got sucked into writing this weird thing on Alex Grey by accident, but it became a very rough sketch of how I understand some aesthetic concepts of the Enlightenment in contrast to the dominate Post Modern ideology of our time. One day we’ll have to go beyond the Enlightenment but for now it remains the most adequate expression of the function of art. I humbly submit this to you in a laughably limited context with the joyful company of trippy Alex Grey. I am also publishing a review from two years ago that went unpublished because… why not. The show was great and should be remembered. I also dug up this old video of art critic Hilton Kramer going up against Peter Plagens, then art critic for Newsweek; Marcia Tucker, then director of the New Museum; and Neal Benezra, then chief curator of the Hirshhorn — on why Contemporary Art is or is not important. I admire and appreciate Kramer’s cranky anachronistic presence in the conversation, even if I don’t 100% agree. Also there’s some market articles in there.

I hope you enjoy it. I deeply value the feedback of my readers and hope that Camel can help spark conversations about what we can do differently as artists, dealers, writers, etc to support an improved artistic environment. Don’t hesitate to comment, message, or join the chat.

ESSAY

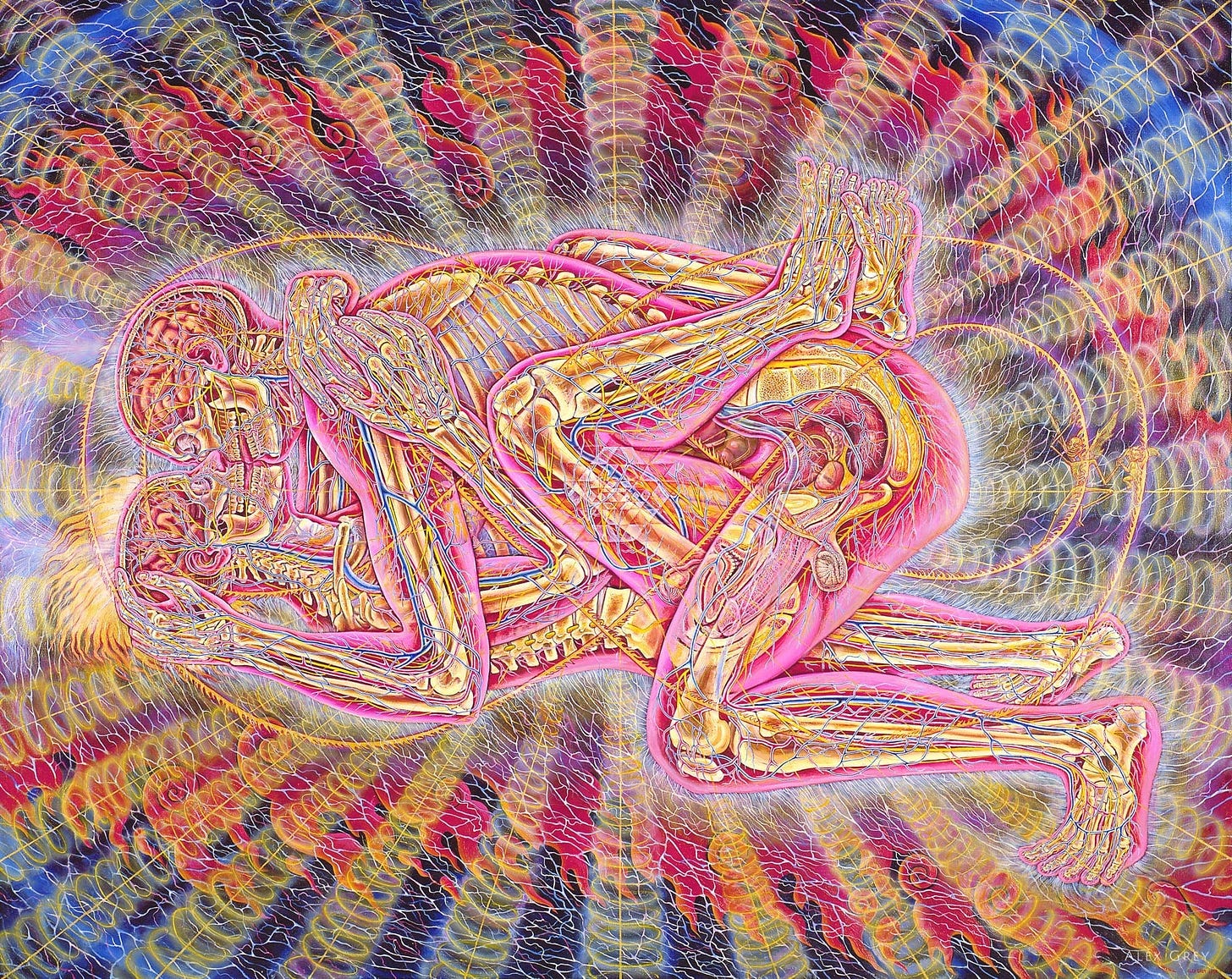

Alex Grey, the artist known for intensely psychedelic portraits and two Tool album covers, posted this video illustrating his concept of the "Visionary Art Process" for attaining transcendental beauty. Let me say right off the bat that to my eyes, a lot of his work sucks. But a little bit of it is good, really good. Or it seems to be, I admit to never having seen it in person. When it comes to the theory of art he proposes in that video, basically I agree with him. He breaks it down into a four step process. For viewing art, aesthetic beauty (the art experience) is attained through technical beauty (the artwork), which is produced by archetypal beauty (the artist) who receives inspiration from transcendental beauty (the source and the object of the whole system). In reverse order we could say that transcendental beauty precipitates down and fills an artist with forms, which then are filtered into objects for a viewer to behold. The whole process is oriented toward the synchronization of its elements with transcendental beauty. This is basically the Enlightenment view of art, with some caveats. Even the idea of art for art's sake basically fits this paradigm, except it simply replaces the transcendental source with the tradition of art itself. This is as good an opportunity as any for me to layout some basics of how I understand the significance of art. I wouldn’t say that my views as expressed here are in their penultimate form. I’m treating this more as an exercise. I intend by the end to make a case for why Grey’s model of aesthetic experience is more or less true and desirable. I will also venture to judge whether his own works live up to the task that his model sets up for the artist. Opposite this model, there is another approach to art that I argue dominates Contemporary Art that has its roots in the 20th century and deserves our scrutiny.

Enlightenment View of Art

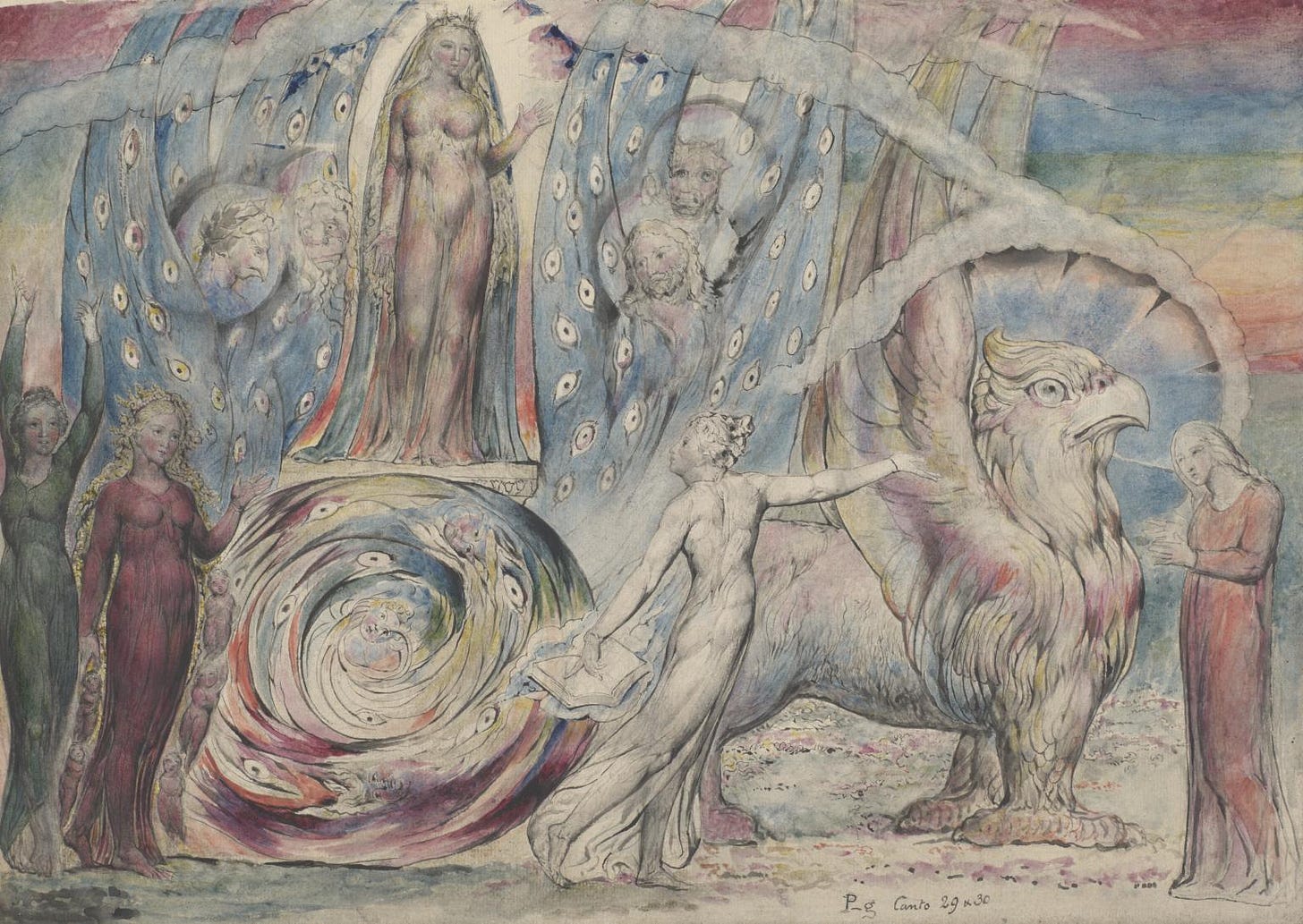

Whether we are dealing with a cosmic divine origin of inspiration or an art historical origin, the process runs basically the same. Either way the viewer of the artwork experiences the artwork as insight. The artwork provides the viewer with a vision of reality that goes beyond the mere material experience of the object of the artwork and enters into either the archetypal terrain of transcendental experience or Hegelian Geistic Historical reality, depending on your worldview.

As it is important for my argument, here is a super rough explanation of Hegel's Geist. If you're familiar with the concept already you can probably skip this paragraph. Geist is the collective subjectivity of History. For Hegel there is a grand narrative, a macrocosmic arc, that spans the whole of human existence that is pushed along by and points towards unfurling human freedom in, through, and over nature. It is the force of the process of human becoming. Most events do not matter, they simply become the past, and are not "History". This, by the way, describes the difference between Art and artifact—all of History is the past but not all of the past is History, just as all Art is artifact, but not all artifact is Art. His aesthetic theory describes significant artworks as those which are capable of both illuminating the characteristics and purpose of this macrocosmic force, and pushing it along towards higher development.

This view that artworks should pursue Geistic quality does not come down to us unbroken, since the modernist project of art for art's sake was misinterpreted beginning in the early 20th century with what I will call, following Hilton Kramer, the “guerrilla modernists”. The core divergence in this misinterpretation has to do with art’s function and domain. We will return to this later in the essay. First, what is art’s function and domain? Kant asserted three faculties of human subjectivity and activity: intellectual knowledge, moral knowledge, and the aesthetic. Intellectual knowledge or "Pure Reason" is what we can know. It’s philosophical, cerebral, testable, provable. Moral knowledge, or "Practical Reason", is how we know it and why we know it and how we use it. Then there is the aesthetic, or the faculty of "Judgement". This is art, intuition, feeling, emotion, et cetera. For example, we can't know that a work of art is beautiful, we feel it to be so. We can't put it to practical use or employ it as the basis of or evidence for morality. It may, however produce insights for how we know the world, how we operate with that knowledge, or reveal characteristics of our morality. Kant thought that the aesthetic was the go-between for the realms of Pure and Practical Reason.

These philosophical assertions were (and to my mind still are) descriptions of our common sense, though it may feel strange to spell such abstract things out philosophically. Today it feels (or does to me) like this must be argued to be true.

As a thought experiment, let’s assume that the Western canon can be known to be beautiful. If it exists in the canon, it is beautiful whether we feel it or not. What makes it so? Works in the canon express progress over their predecessors. How is that progress substantiated? Through the expansion of what can be considered Art. Starting in the modern era, the Romantics overcome the straitjacket of neoclassicism’s rigid formalism by invoking the beauty of dynamism, by placing emotion and nature over reason and order. The Realists overcome the Romantics by expanding the domain of beauty by emphasizing truth over idealized emotions, by depicting modest scenes of quotidian life—workers, peasants, plain nature—instead of the heroic. Perhaps you could say it sought to depict the quotidian as heroic, rendered with little by way of artistic exaggeration. The Impressionists overcome the realists by re-injecting some of that artistic liberty through the manipulation of formal approaches to heighten the sublimity of quotidian scenes. And on and on.

One perspective of this development would recognize these changes as dialectical transformation—both continuity and change, the creation of a third thing out of two interlocked but opposing things. Another might simplistically assume that the lesson of this development is to do something no artist has ever really done before. That the true progress of history is strictly about novelty. But what gets left out in this is beauty. The misunderstanding that took place in the 20th century was the overvaluation of novelty at the expense of beauty—beauty being art’s ability to express the realm of the aesthetic judgement with great power. Beauty in fact is often chased out by self reflectivity, a necessary characteristic of great art that is abused by the guerrilla modernists. The work of the guerrilla modernists all seems very super-ego heavy, and often lacks libido. Reduced to the progress of novelty, the history of art is transformed into a knowable mechanism, rather than a nebulous and evasive challenge to our assumptions about our understanding.

Art and Life

Part of the dilemma revolves around art's relationship to life. For ancient artists, religion, art, and life were fundamentally continuous with one another. The production of art was a fundamentally religious experience, as was its viewing, as was life itself. The depiction of gods made them present. Statues and paintings are worshipped as real, present deities. The reality of the divine and the reality of life were made continuous through art.

We must assume that, for someone like Grey, quotidian life is animated by mysterious forces hidden in plain sight. The artist seeks to capture and distill the traces of these forces through artistic discoveries. The implication is that eternal archetypes underlie experience and await the artist's deployment of their characteristics. But even in Grey's case, the artist is subject to the fundamentally modern discontinuity between religion, art, and life. I would imagine that Grey experiences producing art as a spiritual experience. But it is not as easy to imagine even his most devoted fans worshiping his paintings as gods or spirits, the way a statue of Apollo would have been worshipped in Ancient Greece. This is important because it helps to demonstrate that even in the case of modern spiritual art, it has more in common with modern secular art than ancient religious art.

For a classic modernist, artistic invention consists of intensifying the ephemeral instances of encounters of beauty in life, whether those encounters are with existing artworks or with nature or society. This idea is that the artist’s role is to transform experience through aesthetic innovation, thereby casting collective social values into relief—producing the "ah ha" moment of beauty for the viewer by illuminating for them the deeper texture of their inherited social subjectivity. The modern relationship of art to life is here more explicitly discontinuous. The artworks' power derives from their ability to move beyond the experience from which they were initially inspired. Hegel has a great way to describe this by saying that a good portrait of a person looks more like that person than their actual face. That's because through the work of the artist, supra-physical (or Geistic) characteristics can be built into the image, unlike the random biological circumstances of the formation of a person's facial features, which we might assume have little bearing on who they really are. In both the classically modernist case and the case of someone like Grey, who is basically a Romantic, the production and experience of artworks takes place outside of or beyond quotidian life. The site of their significance is somehow elsewhere. In Grey's terms significance originates in and is oriented towards transcendental beauty. In modernist terms, it is the aesthetic paradigm of the Geist.

The misinterpretation of the guerrilla modernists came when it was assumed that there was not necessarily an origin for artistic inspiration, nor an ultimate purpose toward which the whole thing strove. This liquidated the relationship of art and life rather than intensify it. This stream of artistic investigation treats the idea of beauty, whether divine or historical, with skepticism.

By contrast, in art for art's sake, as we have established, beauty comes from inspiration derived from the existing artistic legacy. That inspiration is inherited by the artist and transformed into new artworks. The viewer experiences both the originality of the resulting product and the continuity with the context from which that artwork was formed. Once the import of the tradition comes under skepticism, context is quickly obliterated. Originality—novelty—becomes an end in itself. The purpose of the artist is transformed from participation in and extension of an artistic tradition into a thoroughly individualized break from all that exists in blind pursuit of the new. We have been calling them guerrilla modernists but I also think of this as the Duchampian school. Hilton Kramer talks about guerrilla modernists in the video at the end of this post. Elsewhere Clement Greenberg has referred to it as the counter-avant-garde.

Kitsch and Avant-Garde

This is all to layout two basic paradigms that we deal with today in the experience of art. The avant-garde pursues beauty through transformation. It makes the aesthetic pursuit the basis and object of its artistic work. Its relationship to tradition is defined by its ability to both inherit and transform. It does not innovate for the sake of innovation, but for the sake of the extension of beauty’s potential. Kitsch is everything else—including the counter-avant-garde, or guerilla modernists, as we have been calling them. It is also the numbing entertainment of the culture industry, and it is the high-class trash that often dominates the art market—it is the majority of what we come into contact with. There's the commercial kitsch industry and the elite kitsch institution. I do think there is still room for great genuinely avant-garde art in today's fine art apparatus, but it's really diamonds in the rough. Most of it is, as Dave Hickey put it, "puritan intellectuals and slavish decorators".

Where does Alex Grey fall? Well, as a basic fact he is an outsider. He was represented by Stux Gallery in the 80s, who also represented Andres Serrano, Doug and Mike Starn, Inka Essenhigh, Dennis Oppenheim, Paul Laffoley and others. And he was in a show at MoMA PS1 around that time. But his career in the gallery circuit didn’t last long. In practical terms he doesn't really operate in the kitsch industry or the kitsch institution. But I thought it especially useful to discuss him in the context of these ideas because he doesn't totally fit aesthetically either. On the one hand he's kitsch in the extreme, he's so genuine about what he paints it's a bit embarrassing and hard to take seriously at times. But on the other he is producing works that check most of my boxes. They seek to move the viewer aesthetically, thereby to provoke the viewer into a new experience of what beauty can be. They strive to sustain and intensify the fleeting moments of aesthetic beauty in life, whether those moments are an LSD peak or an orgasm. They possess modernism's classic "mania for totality" as Arnold Hauser put it. Each work is an image of the macrocosm, they are specific images which tend to explode outwards into a weltanshauungg. They are consistently loud, but at their best they are still nuanced.

His work aims to pursue spiritual experience through aesthetic technique. There is a sense of sport here which makes me suspicious, as if technical expertise directly correlates to artistic successfulness. Ultimately his technical proficiency is not employed as an end in itself but for the purpose of a powerful aesthetic experience. Nonetheless this is where they begin to break down for me. They lack a certain self-reflexivity as objects. Interestingly Grey was influenced by the Viennese aktionists, guerrilla modernists par excellence. I'm sure he was drawn in by their ostensible attempt to resuscitate that ancient continuity between religion and life. This informs the ritualistic context I imagine he works within. But when it comes to the experience of the work that performative continuity fades away. I wouldn't normally invoke Michael Fried, but in his terms Grey's works are too theatrical. They possess sublimity but the ability of the viewer to participate in that sublimity is partitioned off by an invisible fourth wall. The viewer experiences that beauty virtually, not actually. Ultimately, for this reason, I would say Grey is kitsch. Between the Scylla and Charybdis of mere entertainment and puritan intellectualisms, he breaks down near the former.

REVIEW

I first wrote this short review of Orion’s show Faboo at Derosia in 2023. But I never published it. A couple of weeks ago Orion and I gave a walkthrough discussion to a small crowd at Sprüth Magers on their show by Schulze and Salvo. After that I had the idea to finally publish it here with some edits.

Orion Martin is a painting machine painting machines, which is not to say soulless. I can’t help but notice that in his name is concealed the same syzygy of his paintings. This too-perfectness is motific for him. The machines painted are image machines: mechanized symbols, pointing to nowhere in particular or rather for no particular reason. He paints friends, products, abstract shapes, in surrealistic compositions. They are assertively frontal and feel narrative. Martin spent some years in Chicago and the work of the images had a palpable influence. He also recently told me of the influence of Konrad Klapheck on his work, which in retrospect is also very clear.

Martin’s paintings are painstakingly executed, but the task of painting itself is for a particular reason: to image the symbol, and with as little distraction or interruption as possible. The drama of the works comes from the quality of light, the surprise of the compositions, the objects he includes in these portraits. Sometimes they feel stately, other times sterile and scientific, elsewhere graphic and indexical. his

The fourth wall is broken in a mystical way. It’s ancient-feeling. More specifically it has more in common with Egypt than Greece or elsewhere. This is explicit in the positions of the figures in (the painting with Parker) but is implicit throughout. The compositions are imbued with meaning but the meaning itself is elusive and archetypal, like hieroglyphs they say something but remain irreducible to intellectual or moral logic.

But the purity of the paintings isn’t total. The most apparent departure being the residual pencil markings that suggest the blueprint of the paintings. There’s a metaphor which is all too obvious. The pencil marks give shape to the compositions: they are the underlying animating geometry. In like way the compositions of the paintings themselves — in their archetypical drama — seem to suggest themselves as formulaic ingredients for reality per se.

It was really a lucky accident that I thought to publish this in the same issue as my essay on Alex Grey. I hadn’t thought of the two artists together before. I think Martin possess some similar traits to Grey, with some major differences. Both have a remarkable level of technical skill that they employ in order to produce aesthetically persuasive images. But for Martin it is clear that he is invested in art as an activity. There’s much more of that classic art-for-art’s-sake attitude. Cosmic themes, if there are any, are inventory to be used towards an artistic end. In Grey’s case it’s the reverse: artistic material is used for a spiritual end, and so they have a hint of didacticism in them, and thus fall short as works of art. This show by Martin has stuck with me since I saw it. He is in my opinion among the most underrated artists working in LA today.

MARKET DIGEST

Some stuff about shifting gallery structure, closures

Clearing Closed. ArtNet

More on Blum closure. Cultured Mag.

Kasmin and Clearing Galleries Announce Closures. Hyperallergic.

More stuff about where falling sales is hitting the market this year, specifically with regards to secondary. If this interests you, check out Camel #2.

The Worst Performer in Billionaires’ Portfolios? Trophy Art. WSJ.

Art Sales Slump at Auctions. Barrons.

Art market lost its grip on price. Artnet.

Art market spring update. Bank of America.

Virtual exhibitions? The Art News Paper.

We used to talk about web3 having three components: AI, crypto, and VR/AR. Tech giants poured billions into developing these, but so far only AI and crypto have found a real market. Especially during Covid the drive for VR/AR seemed urgent from a reward perspective. The truth is that there is far less consumer interest in it than AI and crypto which each have enormous potential to transform commerce and industry. Meta most obviously threw it's weight behind VR/AR but none of these products have come to fruition, apart from their AR Ray Ban collab that no one uses. Apple's AR goggles are probably their worst performing hardware product. A friend of mine who is in the know in Silicon Valley told me in 2022 that there was some level of panic or disorientation coming to the surface at Apple as they were realizing that their immense VR department was potentially fruitless. Personally I don't believe AI is intelligent. AI is the same marketing gimmick as "smart" devices. I still think its potential to transform the world is real. It is the general purpose technology of our century, so far. Crypto has similarly profound implications for society, from fractional tokenization, to CBDCs or privately issued stablecoins, to logistics tracking and fast, low-cost global transactions. VR/AR might have some good use potential in military, medical, industrial, or construction contexts, but it's not really there yet. Will it be useful for art? I'm deeply skeptical. AI can make the production, distribution, and appraisal of art more efficient and accurate. Crypto can make its accessibility more broad. VR/AR is just fancy photography at best. I don't think you can close the sales gap with fancy photography. You'd be better off looking for ways to fractionalize ownership of high value works using crypto. Or by using AI to discover opportunities to make your operations leaner and your sales more targeted.

VIDEO

I first saw this video a few years ago and it really struck a chord with me. Hilton Kramer is problematic for a number of reasons, he's not a critic I would easily march alongside into battle. That being said I find his crankiness often justified and I admire his clarity when it comes to sniffing out turds and calling a spade a spade. This video is from 1995 when there was certainly more room for the outrageous at the institutional level. If we were to take Marcia Tucker and Neal Berenza as the voices of the general American fine art institution then certainly there has been deeper conservatism when it comes to the shocking. I’m reminded of the controversy of Jordan Wolfson’s “Real Violence” at the Whitney Biennial in 2017 as a potential exception. But by and large there is a lot of safe neo-avant-garde art. Or maybe we are more numb to shock. I’ll have to think about it.

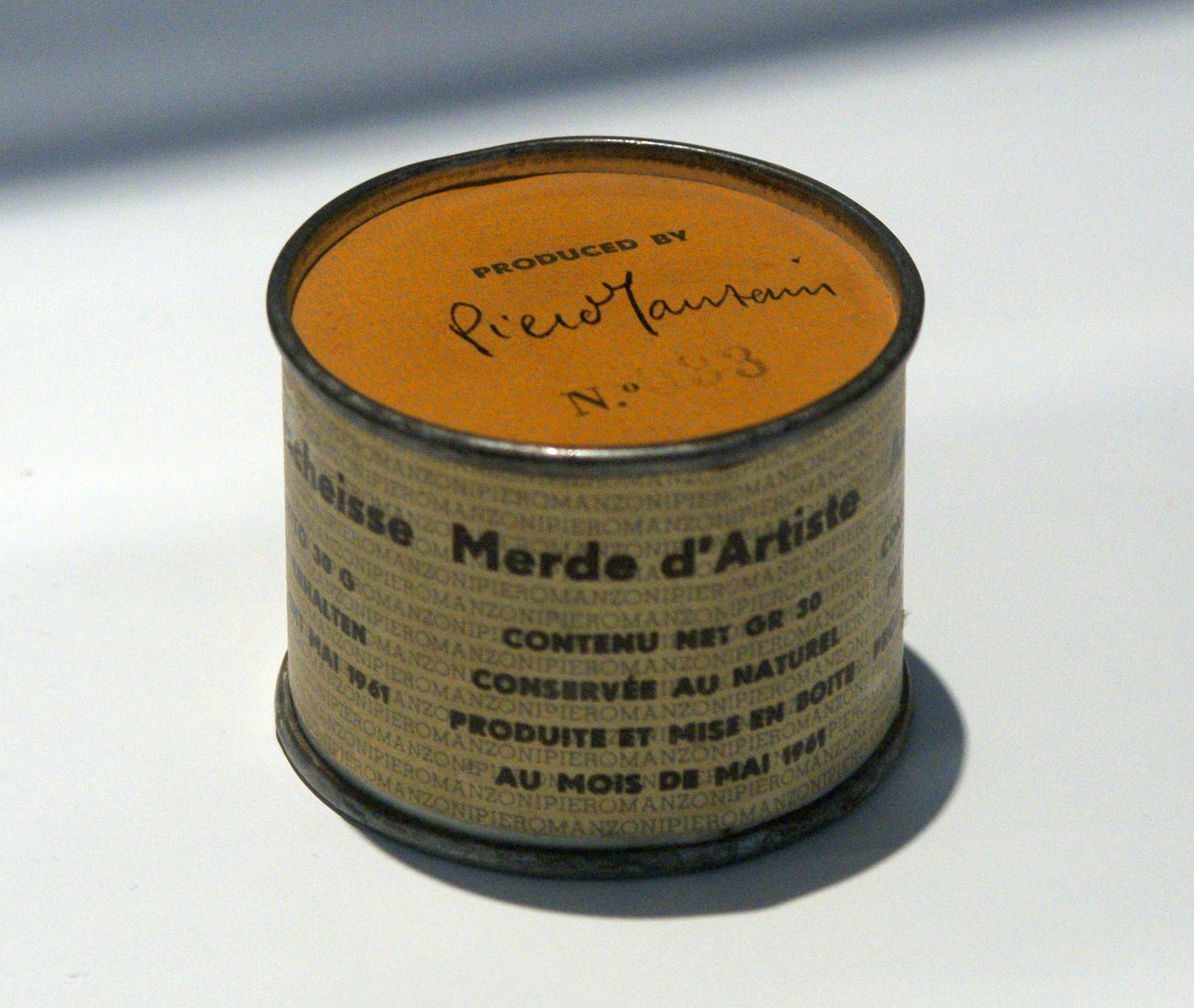

I like to think about neo-avant-garde art as the epigones of what Kramer refers to as the guerrilla modernists, specifically starting with the Dadaists. This is an approach to aesthetic experience that seeks confrontation with the definition of art as an end in itself. Kramer fudges the issue when he says what sets contemporary art apart is that its outrageousness is immediately embraced. More accurately, what sets the guerrilla modernists and the neo-avant-garde (Duchamp to Vito Acconchi to Bruce Nauman to Paul McCarthy to Mike Kelly to Jordan Wolfson) apart is that the built in shock value serves little to no further purpose. The duration of this kind of experience is rather short. It provokes a confrontation with the viewer and then recedes. By contrast the traditional modernists (literally traditional by account of their studied relationship to their artistic inheritance) mobilized the shock of formal originality towards a renewed experience of beauty. And by beauty here I refer to the true meaning of beauty which has no bias towards agreeability but rather expressed the sustained and profound qualities of the experience of great art. I also call that art which derives from guerrilla modernism Duchampian art for he was its greatest expression, and among the earliest. This kind of art, as Peter Fischli once pointed out, rests on the intellectual talents of a chessmaster. It represents to me a shift in emphasis in the importance of artistic experience from the soul to the head. The Contemporary Art epoch is, to my mind, cerebral more than anything else. It is rooted in a short duration initial provocation, after which the need for the presence of the actual artwork recedes. Since its provocational power rests often on novelty, it also tends to expire rather quickly. This paradigm became a vicious cycle of competitive novelty, eating itself up without much regard to Teleological purposiveness.

We are no longer in the epoch of Contemporary Art, though we haven't yet admitted that because we aren’t quite sure where we are at all. We are shipwrecked.

Thank you for reading. If you'd like to be removed from the newsletter please say so in a reply or feel free to unsubscribe. If you have any comments or questions or disagreements, please send me a message. We also have a chat going on Substack if you’d like to join the conversation.

Peace,

Grant

grant.edward.tyler@gmail.com

https://granttyler.cargo.site/

www.instagram.com/grantedwardtyler